Could a Georgetown Lab Finding Lead to New Treatment in Pancreatic Cancer?

Posted in Lombardi Stories | Tagged cancer, cancer research, clinical trials, immunotherapy, pancreatic cancer, translational research

(February 2, 2024) — In the past decade, immunotherapy has offered breakthrough therapies for many cancers that had previously been considered difficult — or even impossible — to treat. One cancer that has eluded the promise of immunotherapy so far, however, has been pancreatic cancer.

This highly aggressive cancer has few treatment options; in most cases, it’s caught too late for surgery, and neither immunotherapy nor radiation are effective, leaving only two toxic chemotherapy cocktails in oncologists’ arsenals. As a result, it’s among the deadliest of cancers, ranking as the third leading cause of cancer deaths, even though it’s relatively rare.

Now, for the first time, new research by Georgetown scientists shows potential to make immunotherapy effective in pancreatic cancer by combining it with a drug that makes cancer cells more responsive to immunotherapy. The research is now in a phase 2 clinical trial being tested in human patients.

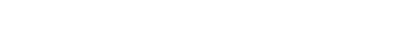

In previous mouse studies, researchers led by Louis Weiner, MD, director of Georgetown University’s Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, saw that the new drug, when combined with immunotherapy that almost never works in this disease, empowered the animals’ natural immune systems to fight back against the cancer, slowing or even stopping tumor growth.

“It was remarkable,” said Weiner, senior author of the publication that supported the launch of the clinical trial. “The animals experienced the complete disappearance of their tumors, and the cancer didn’t come back.”

In fact, when researchers tested the mice by reintroducing them to pancreatic cancer cells six months later, they were able to fight off the cancer and prevent it from taking hold.

“It suggests that the medications themselves are working, but they’re also training the immune system to reject the cancer cells,” said lead author Allison Fitzgerald, MD, PhD (M’23, G’23), who co-authored the paper while at Georgetown Lombardi and is now an internal medicine resident at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. “This suggests it could be a durable option for patients.”

‘Heating Up’ Cold Tumors

One reason immunotherapy isn’t effective is because pancreatic cancer features so-called “cold” tumors that are not detectable by the immune system. This occurs in part because pancreatic cancer cells have relatively few genetic mutations compared to other cancers, explained the clinical trial’s principal investigator, Benjamin Weinberg, MD, an associate professor of medicine, member of Georgetown Lombardi and attending physician at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital.

“They look very much like normal pancreas cells, so the immune system is not very interested in going after them,” he said.

Pancreatic cancer also hijacks the body’s wound-healing ability and surrounds itself with thick scar tissue, walling itself off from immune attack. At the same time, it triggers changes in the microenvironment around the tumor, creating conditions that are inhospitable to immune cells while supporting tumor growth.

For the new research, scientists started by looking at an agent called BXCL701, which was being tested in other cancers, as a way of “heating up” cold tumors by altering the tumor microenvironment, making it more receptive to immune cells. Researchers hoped BXCL701 would enable the body’s natural immune system to recognize and start attacking pancreatic cancer cells — potentially making the cancer vulnerable to immunotherapy, which supercharges the immune system’s ability to attack.

“When these approaches work, they can work quite well, and be quite durable — unlike chemo, which is quite toxic and not durable,” Weinberg said.

Translating Research from Lab to Patient

In the mouse study, researchers took a closer look at why the animals were responding to treatment. They found evidence that tumors in the treated mice had been flooded by “natural killer” immune cells, a sign that the drug had accomplished its goal of making cancer cells receptive to the immune system.

At the same time, they were surprised to find that the amount of collagen in the scar tissue surrounding the tumor had been dramatically reduced.

“It led us to think that this drug, in addition to activating the immune system, also has the ability to make it easier for immune cells to maneuver around the tumor, because there isn’t as much collagen blocking their way,” Weiner said.

The team published their findings in 2021 and moved quickly to start a clinical trial, a process that was accelerated because BXCL701 had already been found safe in other studies.

Fitzgerald said the study points to the importance of translational research in taking discoveries from the lab and developing them into treatments that can improve the lives of patients.

“I think for Georgetown and for science, it’s pretty exciting to have a paper and take it all the way from cells in a dish, to mice, and then to humans, all within just a couple of years,” she said.

Ending a New Drug Drought

The clinical study combines BXCL701 with pembrolizumab, an anti-PD1 immunotherapy drug that is already approved by the FDA to treat a variety of other cancers. Researchers are testing the combination in pancreatic cancer patients who have already received chemotherapy, Weiner explained.

“This is a patient population whose cancer has an exceedingly poor prognosis,” he said, adding that the early clinical results are very encouraging, and that this treatment program has the potential to be a game-changer for patients with advanced pancreatic cancer.

Weinberg said the study is important because pancreatic cancer has historically been a “graveyard” for drug development. Oncologists have gone decades without new treatment options, and overall survival for patients with advanced disease hasn’t improved in more than 10 years. Recent developments have focused on releasing updated versions of the same chemotherapy drugs that have been used for years.

“It’s exciting that we’re seeing some novel immunotherapy drugs. For the first time, there is some real hope on the horizon,” Weinberg said.

In addition to monitoring for patient response, researchers will take tumor biopsies and blood samples over the course of treatment to better understand the mechanism of how the drug combination works in humans, Fitzgerald added.

“There’s [laboratory] bench-to-bedside, but there’s also bedside back to bench,” she said. “We want to take that human information and go back to the lab and try to make it even better than when we started.”

Ilima Loomis

GUMC Communications

Weiner Lab photos by Phil Humnicky/Georgetown Univ.

For more information about this study, please contact Princess Jones at 202-687-3091 or paj24@georgetown.edu.

Weiner’s research is supported in part by BioXcel Therapeutics, Inc., the company developing BXCL701. Support for his work is also provided by the Edwin and Linda Siegel Family Foundation. Weiner reports no other conflicts related to the study. Weinberg reports having no personal financial interests related to the study. The clinical trial is supported by BioXcel Therapeutics, Inc. and Merck.