The Arts Through the Lens of Health Care at Georgetown Lombardi

Posted in Lombardi Stories | Tagged Arts & Humanities Program

(August 16, 2019) — On one floor of MedStar Georgetown University Hospital, musician Karen Ashbrook played hammered dulcimer while a patient was undergoing a difficult procedure. Halfway through, the patient gave Karen the thumbs-up signal that she was focusing on the music instead of the medical intervention.

On a different floor, visual artist Lauren Kingsland gave a writing journal to a man unable to speak because of tubes in his mouth. He wrote in it, “God bless you! This means more than you know.” Then he took Kingsland’s hand and put his other hand to his heart and patted it three times.

Harpist Miriam Gentle didn’t know that the hospitalized man she was playing for had, in his career as a psychologist, worked to humanize the hospital experience for children. In the 1960s, now-88-year-old Milton Shore convinced hospitals to allow parents to be with their sick children, reducing stress on families and caregivers. He became nationally known as an influential and tireless advocate for children.

Shore had been in the Georgetown hospital for days, fighting recurrent pneumonia. Gentle played the folk music he loved, and Shore responded by raising and lowering his eyebrows.

“It was comforting and powerful in so many different ways and was a tribute to the work he did for children and families during their hospital experience,” says his daughter, Lisa Shore. “The Arts and Humanities Program has the potential to impact so many others in a positive way.”

Reclaiming Identity

All of this engagement is the work of the Georgetown Lombardi Arts and Humanities Program, which started three decades ago with a $50,000 grant to improve the look and feel of the Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center. A $1.5 million endowment by the Robert M. Fisher Memorial Foundation created the Cecilia F. Rudman Arts and Humanities Fund in 2006 and provided a part-time director for an expanded program. A $3 million endowment from Frederick and Diana Prince in 2010 enlarged the program even further — as have many donations, including Lisa Shore’s.

All of this support has led to a program that aims to “create the hospital as a 21st century arts space,” says the program’s director, Julia Langley. Since taking the helm in 2014, Langley has been building a “cohesive and integrated music, dance, expressive writing, visual and performance arts sanctuary” for patients, medical staff, caregivers and visitors.

“When people come through the door of the hospital, they are seeking wellness. Our job is to help them navigate the difficulties of each stage of illness by embracing the arts. It is part of MedStar Georgetown University Hospital’s goal of cura personalis, or care for the whole person,” says Langley. “We encourage all of our communities to express themselves through the arts, whether that is by listening to music, looking and engaging with art, moving and/or writing, if they want to.”

Langley says the task is a special challenge in these days of devices. “Everyone is looking down. We want them to look up.”

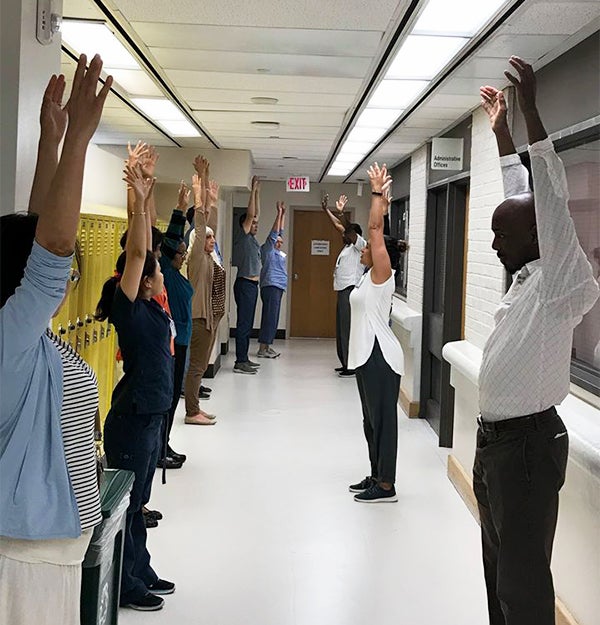

And there is much to see and do. Original, vibrant, sometimes humorous art — “Willam Wegman gave us a photograph of a Weimaraner in a wedding dress. It’s hilarious and wonderous!” she says — covers the walls, a poetry café springs up annually, beaded bracelets and origami cranes are made to show love and support, all matter of stringed instruments resound, professional dancers dance, hundreds of staffers enjoy five-minute guided stretch breaks each week, and a yoga master conducts three 30-minute yoga classes in the seventh-floor hallway weekly.

Future planning includes the addition of theatrical performances of original material.

The quality of the programming is very high; only professional artists, musicians, and dancers participate. “We are working to professionalize the field of arts in health,” says Langley. “And to embed the work directly into patient and staff care. We know that care doesn’t end with a hospital discharge. We need to give people the tools to continue with physical, mental and emotional self-care at home.”

Studying Benefits

True to the appointment she holds as an instructor in Georgetown’s School of Medicine, Langley has also put an emphasis on finding scientific evidence that these programs help patients, if not their families and caregivers. Work has already been done on the effects of writing and music, and Langley says the program, in general, “will always honor its roots by its dedication to examining the benefits we can offer to cancer patients and survivors.”

And to examine the link between music, movement and health, Langley has established research partnerships with scholars at the Karolinska Institute and the Royal College of Music in Stockholm, Sweden, as well as with the University of Florida and the Scottish Ballet. “We are the only hospital in the country to have a strong movement-in-medicine program, and so we are ideally situated to gather evidence for its value,” she says.

She is also now working with several Georgetown neurologists to study the effect of sustained movement on people with multiple sclerosis. “We regularly have 15 to 18 men and women who come to the course we developed, and they say it not only helps with stiffness and muscle aches, but it also breaks their isolation and gives them a community of like-minded people to be with,” Langley says. “The social bonds turn out to be unbelievably strong.”

“It’s a challenge to study art through the lens of hard science,” Langley says. “But I and many others see the evidence, however anecdotal it is, every day on the faces that, for many reasons, populate this hospital.” And that keeps the fire burning to build a strong research base and prove the efficacy of integrating the arts into health care, she adds.